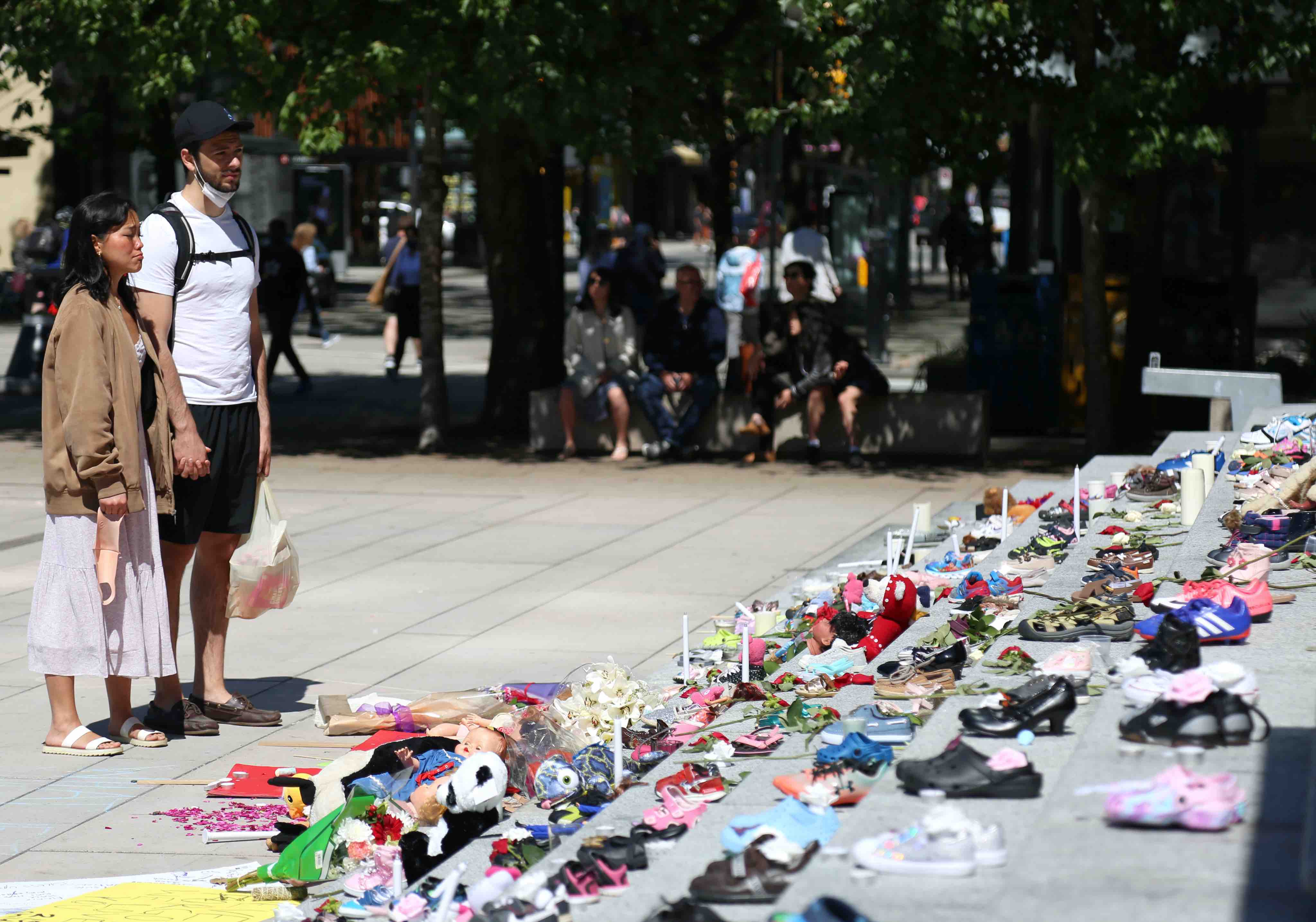

215 Indigenous Children’s Remains Have Been Found At A Former School To Assimilate Them In Canada

A mass grave containing the remains of 215 indigenous First Nation children, some as young as three years old, has been discovered at a former school to assimilate indigenous children in Canada.

A mass grave containing the remains of 215 indigenous First Nation children, some as young as three years old, has been discovered at a former school to assimilate indigenous children in Canada.

The discovery at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Colombia, which closed in 1978, was made with a ground-penetrating radar.

“We had a knowing in our community that we were able to verify,” the chief of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation said in a statement on Thursday May 28. “To our knowledge, these missing children are undocumented deaths.”

The causes and timings of the children’s deaths are not yet known, and the First Nation is working with museum specialists and the coroner’s office to establish them, according to the BBC.

The school, established in 1890 under the leadership of the Roman Catholic church, was part of a Canada-wide network of residential schools set up to forcibly separate indigenous children from their families and assimilate them, according to Reuters.

A six year investigation into the system in 2015 found that it constituted “cultural genocide”.

It revealed the physical abuse, rape, malnutrition and other atrocities experienced by the at least 150,000 children who attended the schools between the 1840s and the 1990s.

The report also found that 4,100 children died while attending residential schools, but the deaths of the newly discovered 215 children appears to have been undocumented.

The Canadian government formally apologized for the system in 2008.

Following the news of the discovery, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau tweeted that it was “a painful reminder of that dark and shameful chapter of our country’s history.”

Indigenous communities have long believed mass graves of residential school students existed, but it took decades to prove, according to the Guardian.

The Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation said it is also reaching out to the home communities whose children attended the school and expect to have preliminary findings by mid-June.